Rising Up and Reaching Out: Black Solidarity Among the Watts Community by Antoinette Golmon

- Watts72

- May 16, 2019

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 6, 2019

The anniversary of the Watts riots, 7 years prior, spearheaded an act of solidarity, through the utilization of various genres of music, such as gospel, jazz, and R & B. Under the banner of “black nationalism,” notions of pride and self-determination were solidified, galvanizing an urgency for racial cohesion, inducing social change. Al Bell, the last president of Stax records, viewed the event as an opportunity “to create, motivate, and instill a sense of pride in the citizens of the Watts community."[1]

Footnotes:

[1] Ferguson, Kevin. "Remembering Wattstax, One of LA's Largest Music Festivals." Southern California Public Radio. October 14, 2012. Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.scpr.org/programs/offramp/2012/08/24/28079/40-years-ago-wattstax-festival-brought-112000-afri/.

From the beginning, the idea of Wattstax was grounded in inspiring black nationalism. Prior to emerging into the well-known concert, as we know it today, the inspiration emerged after the Mafundi Institute, a black nationalist arts group in southern California, reached out to the director of Stax’s West Coast center, hoping to gain sponsorship from the label and hold a concert, for the arts group to aid the community, provide support, and get the community involved. Forest Hamilton, Stax West Coast director, looked for ways to make the event appeal on a more national level, suggesting bringing superstar Isaac Hayes onboard, finally settling on involving various artists on the label. Although the Mafundi Institute would take a back seat as. Wattstax began organizing the ideas to promote black unity and community involvement would remain major players in the project’s efforts.[2]

"Under the banner of “black nationalism,” notions of pride and self-determination were solidified, galvanizing an urgency for racial cohesion, inducing social change."

Footnotes:

[2] Scott Saul, ""What You See Is What You Get": Wattstax, Richard Pryor, and the Secret History of the Black Aesthetic," Post45, August 12, 2014, accessed May 31, 2019, http://post45.research.yale.edu/2014/08/what-you-see-is-what-you-get-wattstax-richard-pryor-and-the-secret-history-of-the-black-aesthetic/.

Source: Source: https://www.kcet.org/shows/departures/revisiting-the-1965-watts rebellion-relics-of-fire

The successful music label could have provided all the necessary funds necessary to host the event. However, by charging a $1 tax deductible admission fee it served a better function. With the fee being relatively small, $1, nearly all residents could afford it. By allowing residents to give towards the cause, they were inclusive of rebuilding and benefitting the community regardless of race, class, or gender, ultimately uniting over 100,000 individuals. 100% of funds raised were given to the Watts summer festival, which then funneled monies directly back to support community organizations and programs, such as the sickle cell anemia program, Watts Labor Community Action Committee, and the MLK hospital.[3] The inclusion of wealthy and successful African American performers helped to strengthen the bond of black solidarity, despite class and gender differences, encouraging less fortunate individuals to uphold racial pride and self-love, regardless of their social standing and demanding to be heard.

While the event gathered local residents and promoted a cultural celebration of black fellowship and capabilities. The concert itself exerted a notion about the capabilities of black Americans, specifically the idea that black individuals and businesses had the ability to succeed in a dominate white world. The music Stax artists created was among the most eccentric music around during the 60’s and 70’s with beats that were hard not to dance too. Not only did the music promote dance, it promoted political activism and embracing the culture of various black inspired genres, such as jazz and funk.

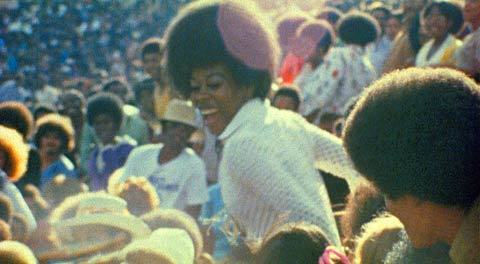

According to historian George Nelson, Wattstax represented “a symbol of black-self-sufficiency.”[4] Although it was not completely all black run, it highlighted the success that black culture is able to obtain, along with the widespread acceptance within society. The atmosphere the crowd experienced elevated moral as patrons were coming together like never before. It was the only time that residents were able to escape the city streets collectively and forget about the troubles that were outside the gates of the arena. For the remainder of the night the crowd was able to focus on their self-worth, enjoyment, and the social atmosphere of dancing, singing, eating, and putting differences aside to celebrate the sense of black pride and celebration that was emitting from the stage in the crowd. It was in this arena the Watts community were able to not only give to their community but gain a new sense of self. Rich or poor, old or young Wattstax created a sense of equality among African Americans that night and its impact has pushed for social change.

Footnotes:

[3] "The Zenith of Soul Music: Wattstax, August 1972," Facing History and Ourselves, accessed May 31, 2019, https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/video/zenith-soul-music-wattstax-august-1972.

[4] "The Pop Festival"; 2015, doi:10.5040/9781501309038.

Photo source:

Happy crowd at Wattstax: http://bowdigs.blogspot.com/2016/02/wattstax.html

Comments